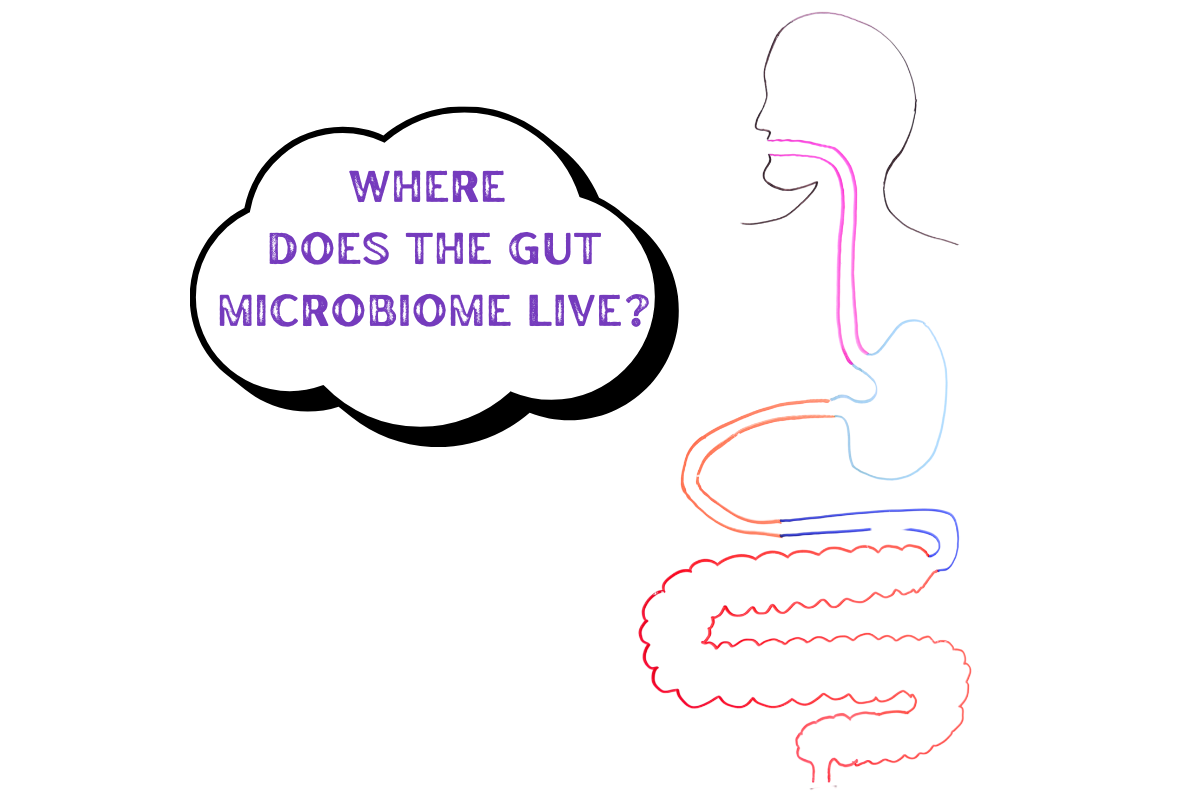

Where is the Microbiome? A Journey Through the Gut

The gut microbiome is a dynamic, complex ecosystem that plays a crucial role in digestion, immune function, and overall health. However, many discussions around gut health focus primarily on the large intestine, overlooking the fact that microbial populations exist throughout the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract. These populations vary dramatically depending on their location, shaped by factors such as pH, water content, and nutrient availability.

This blog will take you on a scientific journey through the gut, from the stomach to the large intestine and colon, to explore how each section of the GI tract influences microbial composition.

1. The Stomach: A Harsh, Acidic Barrier

The stomach is the first major stop in the digestive tract, serving as a highly acidic environment designed to break down food and kill harmful pathogens.

Key Characteristics of the Stomach Environment:

-

pH: Extremely acidic, ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 due to gastric acid secretion.

-

Water Content: Varies widely, water rapidly leaves, remaining food is mixed with gastric secretions to create chyme (a semi-liquid mass).

-

Food Composition: Food is primarily broken down into smaller components, with proteins being denatured and fats beginning digestion.

Microbial Presence:

Due to the harsh acidity, the stomach harbours very few bacteria, with only acid-tolerant species such as Helicobacter pylori able to survive in significant numbers. Most ingested microbes do not survive passage through the stomach unless they are acid-resistant or physically protected from exposure to the acid.

-

NUMBERS: 10 - 1000 bacteria per ml.

2. The Upper Small Intestine: A Transition Zone

The duodenum and jejunum, the upper sections of the small intestine, mark a transition from the acidic stomach environment to a more neutral and enzymatically active digestive system.

Key Characteristics of the Upper Small Intestine:

-

pH: Gradually increases from 4.0 to 6.5 as bile and pancreatic enzymes neutralise stomach acid.

-

Water Content: Higher than in the stomach, as secretions from the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder mix with chyme.

-

Food Composition: Rapid digestion of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats begins here, with nutrient absorption starting in earnest.

Microbial Presence:

While bacterial density remains low compared to the lower gut, certain facultative anaerobes, such as Streptococcus and Lactobacillus, thrive here. Microbial diversity remains limited due to the rapid flow of food and antimicrobial bile secretions.

-

NUMBERS: 1,000 - 10,000 bacteria per ml.

3. The Lower Small Intestine: Preparing for Fermentation

The ileum, the final section of the small intestine, plays a key role in absorbing nutrients and transitioning undigested food into the large intestine.

Key Characteristics of the Lower Small Intestine:

-

pH: Ranges from 6.5 to 7.5, approaching neutrality.

-

Water Content: Remains relatively high, aiding in digestion and nutrient absorption.

-

Food Composition: Absorbed nutrients leave behind dietary fibres and resistant starches that will undergo fermentation in the large intestine.

Microbial Presence:

More diverse species appear, including Bacteroides, Enterococcus, and Clostridium. These bacteria start pre-fermenting certain fibres that will be further metabolised in the colon.

-

NUMBERS: 10,000,000 - 100,000,000 bacteria per ml.

4. The Large Intestine and Colon: The Microbial Hub

The colon is the true powerhouse of the gut microbiome, hosting the most diverse and dense microbial communities.

Key Characteristics of the Large Intestine and Colon:

-

pH: Slightly acidic to neutral, ranging from 6.1 to 7.9.

-

Water Content: Lower than in the small intestine, as water is reabsorbed to form solid faeces.

-

Food Composition: Contains indigestible fibres, resistant starches, and microbial byproducts that are fermented by gut bacteria.

Microbial Presence:

This region houses 95% of the total gut microbiome, making it the most densely populated microbial ecosystem in the body. The diversity of microbes is also at its highest, with dominant groups including Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria. These bacteria play a crucial role in:

-

Fermenting dietary fibre to produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which support gut health.

-

Synthesising vitamins such as B12 and K.

-

Modulating the immune system and protecting against harmful pathogens.

-

NUMBERS: 100,000,000,000 - 1,000,000,000,000 bacteria per ml

Why Understanding Microbial Distribution Matters

The variation in microbial populations across the GI tract highlights why one-size-fits-all probiotic solutions may not be effective. Since different bacteria thrive in different gut regions, personalised approaches to gut health, including targeted probiotics and diet modifications, may be necessary to optimise microbiome balance.

Moreover, relying solely on stool samples to assess gut microbiome health can be misleading. As discussed, microbial composition changes significantly between the small and large intestine, and faGeces represent only the final stage of digestion rather than the complete picture.

Conclusion: The Microbiome is Everywhere—but Not Uniform

The gut microbiome is not confined to one location but varies across the digestive system in response to pH, water content, and food composition. Understanding these variations can help inform better dietary choices, more effective probiotic formulations, and more accurate gut health assessments.

As research continues, the future of gut health may move toward more precise location-specific interventions, improving how we nurture and optimise our microbiomes for better overall health.

Watch our video showing the location of you gut microbiome... https://www.instagram.com/p/DGvTHgotFdB/